Fentanyl is an extremely potent opioid that has driven a surge of overdose deaths over the past decade. For many people, traditional detox and counseling alone are not sufficient to prevent relapse or overdose. That’s where medication-assisted treatment (MAT for fentanyl addiction) comes in: by combining medications with therapy and support, recovery becomes safer and more sustainable.

Why Fentanyl Requires a Different Approach

Fentanyl is not just another opioid, because it’s extremely potent (many times stronger than heroin or morphine) and lipid-soluble, it has intense withdrawal symptoms and it tends to accumulate in body tissues (fat, muscle) and can linger longer than many people expect. This means that even after a person stops using fentanyl, residues may remain and complicate withdrawal and the safe initiation of medications like buprenorphine.

One of the biggest challenges when transitioning someone from fentanyl use into treatment is precipitated withdrawal. This occurs when a partial opioid agonist (like buprenorphine) displaces a full agonist (fentanyl) from receptors and causes sudden worsening of withdrawal symptoms.

In the fentanyl era, the risk of precipitated withdrawal is higher, and the window of safe time before starting MAT can be unpredictable. Many clinicians are now exploring low-dose induction (microdosing) or alternative pathways to reduce that risk.

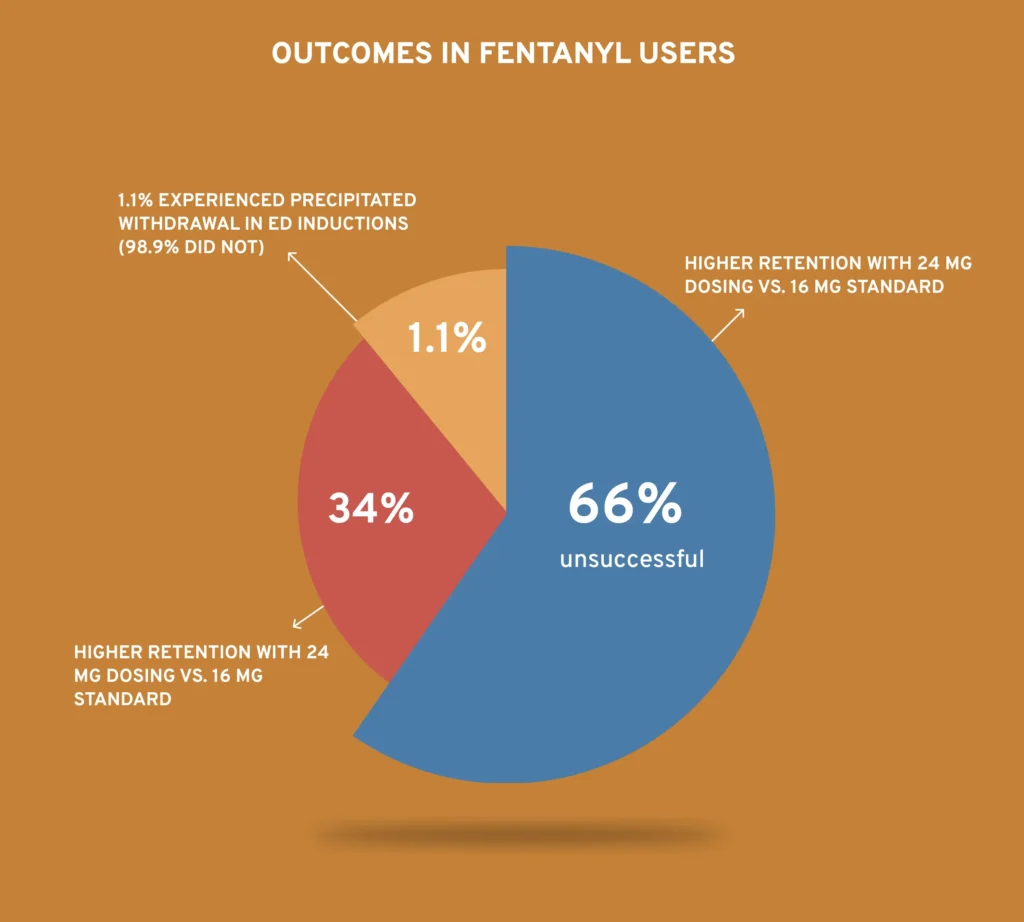

A recent outpatient cohort study evaluated two low-dose initiation (LDI) buprenorphine protocols (over 4 or 7 days) in people using fentanyl. Out of 175 attempts, only 60 (34%) resulted in successful initiation (i.e. transitioning to a maintenance prescription) , a relatively low rate of success. Retention at 28 days was also low (21% for 4-day protocol; 18% for 7-day), showing that induction and early retention remain key hurdles.

Another study found that about 12% of patients using fentanyl developed precipitated withdrawal when starting buprenorphine under standard induction approaches. This suggests that while precipitated withdrawal is not universal, it is a nontrivial risk in the fentanyl setting.

It’s critical to emphasize the extra caution, multiple methods of induction, and the need for monitoring and adaptation.

What Is Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)?

Medication-assisted treatment means combining medication (that helps stabilize brain chemistry, reduce cravings, ease withdrawal) with behavioral therapy and support systems.

In the case of opioid use disorder (including fentanyl addiction), the primary medications used are:

- Methadone

- Buprenorphine (often in formulations with naloxone, e.g. Suboxone)

- Extended-release (XR) naltrexone

These medications help reduce opioid use, prevent overdose, and improve retention in care. MAT does not just “replace one drug with another”, when used properly, methadone and buprenorphine reduce withdrawal symptoms and cravings without producing the high that comes with misuse.

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews show that treatment retention on methadone or buprenorphine is associated with significantly lower all-cause and overdose mortality in people with opioid use disorder.

But with fentanyl, the induction process and early retention are more challenging, so your blog must spell out those details carefully.

MAT Medications: How They Work in Fentanyl Recovery

Methadone for Fentanyl Withdrawal

Medications for Opioid use disorder, Methadone is a full opioid agonist. One of its advantages is that it can be started without requiring a long “washout” period, which avoids some of the risk of precipitated withdrawal. Because of this, methadone is sometimes preferred for individuals who have heavy fentanyl use or have had difficulty initiating buprenorphine. Several reviews and clinical guides suggest that methadone often shows superior retention (people stay in treatment longer) compared to buprenorphine when flexibility in dosage is allowed.

However, methadone treatment is usually tightly regulated: it must be dispensed at a licensed opioid treatment program (OTP), often with daily visits in early phases. This limits flexibility, particularly in rural or underserved areas.

Buprenorphine (e.g. Suboxone)

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist, meaning it activates opioid receptors but to a lesser degree than full agonists.

It has a “ceiling effect” limiting respiratory depression risk, making it safer in overdose settings. Many people prefer buprenorphine because it can sometimes be prescribed in outpatient settings (depending on the country’s regulations) rather than requiring daily clinic visits.

Buprenorphine induction is more complicated. Traditional induction requires a period of abstinence (so that withdrawal has begun) before giving the first dose (to avoid precipitated withdrawal). But because fentanyl lingers, that optimal window is less clear.

Alternative induction strategies, such as low-dose initiation (microdosing / overlap methods), are being tried.

A retrospective study showed that among people using fentanyl, only 34% of attempts at outpatient LDI succeeded in starting buprenorphine. This underscores the reality that while buprenorphine is promising, induction in fentanyl users is less predictable.

Another interesting finding: in a large retrospective cohort of 6,499 patients (in the U.S.) initiating buprenorphine, those started on a higher dose (24 mg) tended to have better retention over 180 days compared to those on the standard 16 mg dose.

Furthermore, a newer analysis suggests that precipitated withdrawal may be less frequent than feared; in one multi-site trial, about 1.1% of individuals experienced PW with standard induction in the emergency department, even when fentanyl was involved. This suggests standard approaches may still be viable in some settings, but with caution.

Extended-Release Naltrexone

XR-naltrexone (e.g., Vivitrol) is a non-opioid antagonist that blocks opioid receptors. Its main limitation in the fentanyl (or any opioid) context is that the patient must be fully detoxed (opioid-free) before initiation, which can be a challenging detox to manage safely. Because of this “opioid-free prerequisite,” many patients cannot tolerate or complete that detox phase, especially with potent fentanyl involvement. The evidence for XR-naltrexone is more limited compared to methadone or buprenorphine.

Thus, XR-naltrexone may be a good option for selected patients, but it is less commonly used as first-line for fentanyl users.

Evidence and Outcomes: How Well Does MAT Work with Fentanyl?

A large comparative effectiveness study of over 40,000 adults with opioid use disorder compared different treatment paths. It found that only methadone or buprenorphine (MOUD) pathways were significantly associated with reduced overdose risk and fewer opioid-related acute care events at 3 and 12 months.

Specifically, MOUD was linked to about a 76% lower overdose risk at 3 months and 59% lower at 12 months compared to no MOUD.

Though many of these studies were done in mixed opioid populations, not always exclusively fentanyl users, they still show that medication-assisted recovery success rates (in terms of reduced overdose risk and improved retention) are significantly better than non-medication approaches.

But fentanyl adds complexity:

- early induction failure

- retention challenges

- higher doses/longer treatment may be necessary.

For instance, as noted above, success rates for buprenorphine microdosing attempts in fentanyl users have been modest (34% initiation success).

A review of comparative trials also suggests that when dosing is flexible, methadone tends to have better retention than sublingual buprenorphine.

That means more people stay on treatment for longer, which improves chances of lasting recovery.

How to Start MAT for Fentanyl Users: Practical Options

Because induction is trickier in fentanyl use, it helps to have a roadmap. Here’s how different paths might be approached, depending on the patient’s situation:

- Standard buprenorphine induction (classical method).

- Wait until moderate withdrawal before administering the first buprenorphine dose (2–4 mg SL).

- Monitor closely, re-dose every few hours if withdrawal recurs, and titrate to a maintenance dose

- In fentanyl users, this method may carry a higher risk of precipitated withdrawal, so clinicians are advised to be cautious.

- Low-dose initiation / microdosing (LDI) / overlap methods.

- Begin with very low buprenorphine doses (e.g., 0.25–1 mg) while overlapping with continued fentanyl or short-acting opioids, then gradually increase.

- The outpatient cohort study mentioned earlier (126 individuals, 175 attempts) had only 34% success overall, showing this method has limitations in real-world fentanyl users.

- Multiple prior failed attempts reduce odds of success further.

- High-dose/accelerated buprenorphine induction (ED settings).

- Some emergency department protocols give higher starting doses (e.g. up to 8 mg) and discharge on 16 mg or more. In a JAMA Network Open trial, precipitated withdrawal was rare even in fentanyl users.

- High-dose induction may help overcome receptor displacement challenges in fentanyl users.

- Methadone initiation.

- Because methadone is a full agonist, it may mitigate the risk of precipitated withdrawal entirely.

- It may be particularly useful for patients with high fentanyl tolerance or prior buprenorphine induction failure.

- XR-naltrexone initiation (in selected cases).

- Only after complete detox and an opioid-free period.

- Not usually the first choice for fentanyl users because of the challenge of safely completing detox.

The Importance of Therapy & Combined Care

Medication is powerful, but treating fentanyl addiction comprehensively means combining medications with psychosocial support: therapy, counseling, peer support, case management, and social services. Evidence consistently shows that outcomes are better when combining therapy with MAT for fentanyl than medication alone.

Behavioral interventions help patients address triggers, coping strategies, mental health conditions, and life stressors that fuel relapse.

Reducing Overdose Risk Through MAT

One of the biggest advantages of MAT is its ability to drastically reduce the risk of overdose. When someone is stabilized on an agonist therapy (methadone or buprenorphine), their tolerance fluctuations are minimized, cravings are reduced, and illicit opioid use drops. As a result, overdose risk falls significantly.

Accessing MAT: Where and How

Recent policy changes, buprenorphine prescribing is now more accessible in the U.S. (the X-waiver requirement has been removed), which means more clinicians can offer treatment. Telehealth has also made it easier to connect with MAT providers, especially for people who live far from clinics.

But access is still uneven. People seeking MAT for fentanyl addiction often run into:

- Stigma and judgment – fear of being labeled an “addict” or facing discrimination at work, school, or even in healthcare settings.

- Limited providers – not every community has opioid treatment programs (OTPs) for methadone or doctors who are confident treating fentanyl addiction.

- Regulatory constraints – some regions still have strict rules on take-home methadone doses or daily clinic attendance.

- Cost and insurance issues – MAT can be expensive without coverage, and not all insurance plans cover every medication option.

- Travel distance – rural patients may have to drive hours just to access care.

- Clinician reluctance – some doctors hesitate to initiate buprenorphine in people using fentanyl due to fear of precipitated withdrawal.

Realistic Expectations: Success, Challenges, and What “Recovery” Means

It’s essential to set realistic expectations. MAT is not a magic bullet, especially in the fentanyl era. Many people require multiple attempts, switching between medications, or extended support in Rehab centers. Retention in care is a major predictor of success staying on MAT longer (6+ months or more) correlates with better outcomes.

What counts as “success” may vary:

- Reduced illicit opioid use

- Fewer overdoses

- Improved quality of life

- Ieintegration into work/relationships

- Abstaining entirely

What is the best MAT for fentanyl?

Methadone and buprenorphine are considered the most effective MAT options for fentanyl addiction because they reduce cravings and lower overdose risk.

What is MAT in opioid treatment?

MAT is medication-assisted treatment, combination of medications and counseling to treat opioid use disorder.

What does MAT stand for in drug terms?

MAT stands for Medication-Assisted Treatment.

What is the new name for MAT?

The newer term is MOUD (Medications for Opioid Use Disorder) to emphasize it is the gold-standard medical treatment.

What are the 3 types of MAT?

The three main MAT medications are methadone, buprenorphine (Suboxone), and extended-release naltrexone (Vivitrol).